Index

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of hereditary-familial retinal degenerations of primary incidence with autosomal dominant and recessive, X-linked and mitochondrial modes of inheritance.

It is a progressive disorder that involves the death of the rods followed by the loss of the cones; although the loss of both types of photoreceptors can occur simultaneously.

Numerous genes have been identified which, when mutated, cause various forms of non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa; are known to date more than 80 gene mutations which cause non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa.

Retinitis pigmentosa and Genetics

Retinitis pigmentosa is extremely heterogeneous, both clinically and genetically, it can be transmitted in an autosomal, sex-linked and mitochondrial manner. The inheritance modes of RP are: autosomal dominant (AD), autosomal recessive (AR), X-linked recessive (XL) and mitochondrial; the relative prevalence of each form varies slightly among the populations studied, although autosomal recessive inheritance appears to be more common, accounting for approximately one third or more of all cases of Retinitis Pigmentosa.

Some genes are specific for the retina or photoreceptors, others have a more ubiquitous expression and function (e.g. mRNA splicing), and still others encode proteins whose function in the retina is not yet fully understood.

Less commonly, Retinitis Pigmentosa occurs as part of syndromes that affect other organs and tissues in the body. These forms of the disease account for 20-30% of cases and are described as syndromic.

The most common form of syndromic retinitis pigmentosa is Usher syndrome, characterized by the combination of vision loss and hearing loss from the beginning of life. Other genetic syndromes are the syndrome of Bardet-Biedl, Refsum's disease, and the Neuropathy-Ataxia -Retinitis Pigmentosa syndrome (NARP syndrome).

Symptoms

Although the course and progression of retinitis pigmentosa show considerable variation between individuals, the disease is typically characterized by specific initial symptoms. Often the first symptom is night blindness, with onset in the first or second decade of life. Subsequently there is loss of peripheral vision and, as the disease progresses, loss of central vision which can lead to complete blindness or severe visual impairment.

In the "classic" presentation of retinitis pigmentosa, the difficulty in adapting to the dark begins in adolescence and the visual loss in the mid-peripheral field becomes perceptible at a young age. However, the age of onset among patients with this disease varies widely; some patients develop vision loss in early childhood, while others may remain relatively asymptomatic until the third / fourth decade of life.

The exact age of onset of retinitis pigmentosa is often difficult to determine because many patients, particularly children, are able to compensate for peripheral vision loss with research. Furthermore, the difficulty in adapting to the dark can remain unnoticed by the patient due to an artificially well-lit night environment. In general, Retinitis Pigmentosa subtypes that manifest early in life tend to progress more rapidly.

Retinal alterations

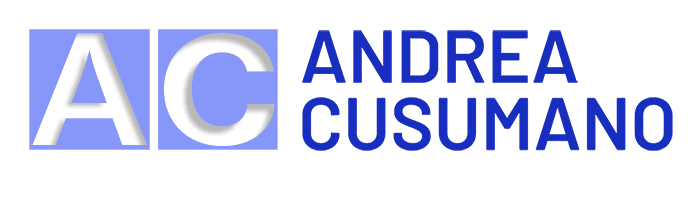

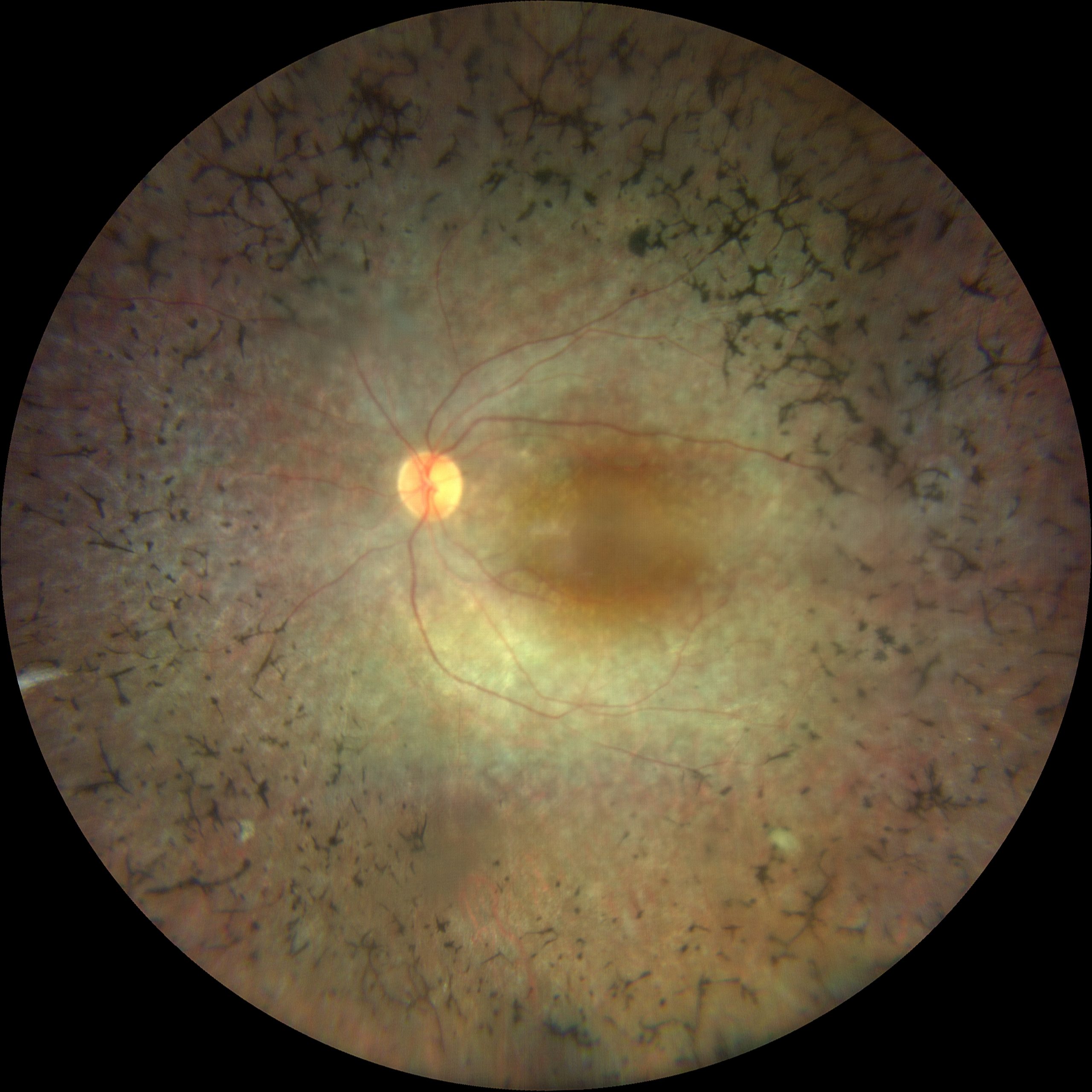

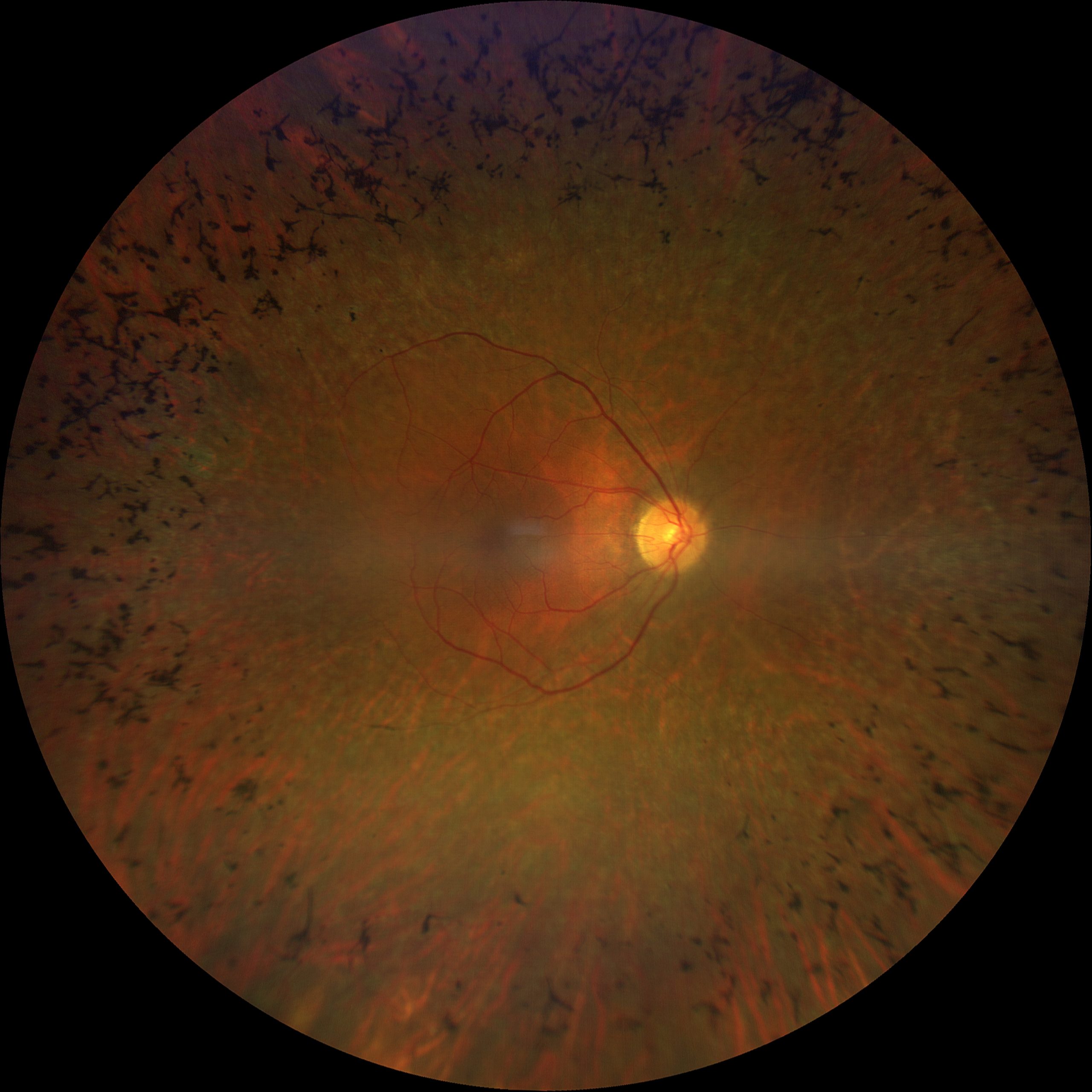

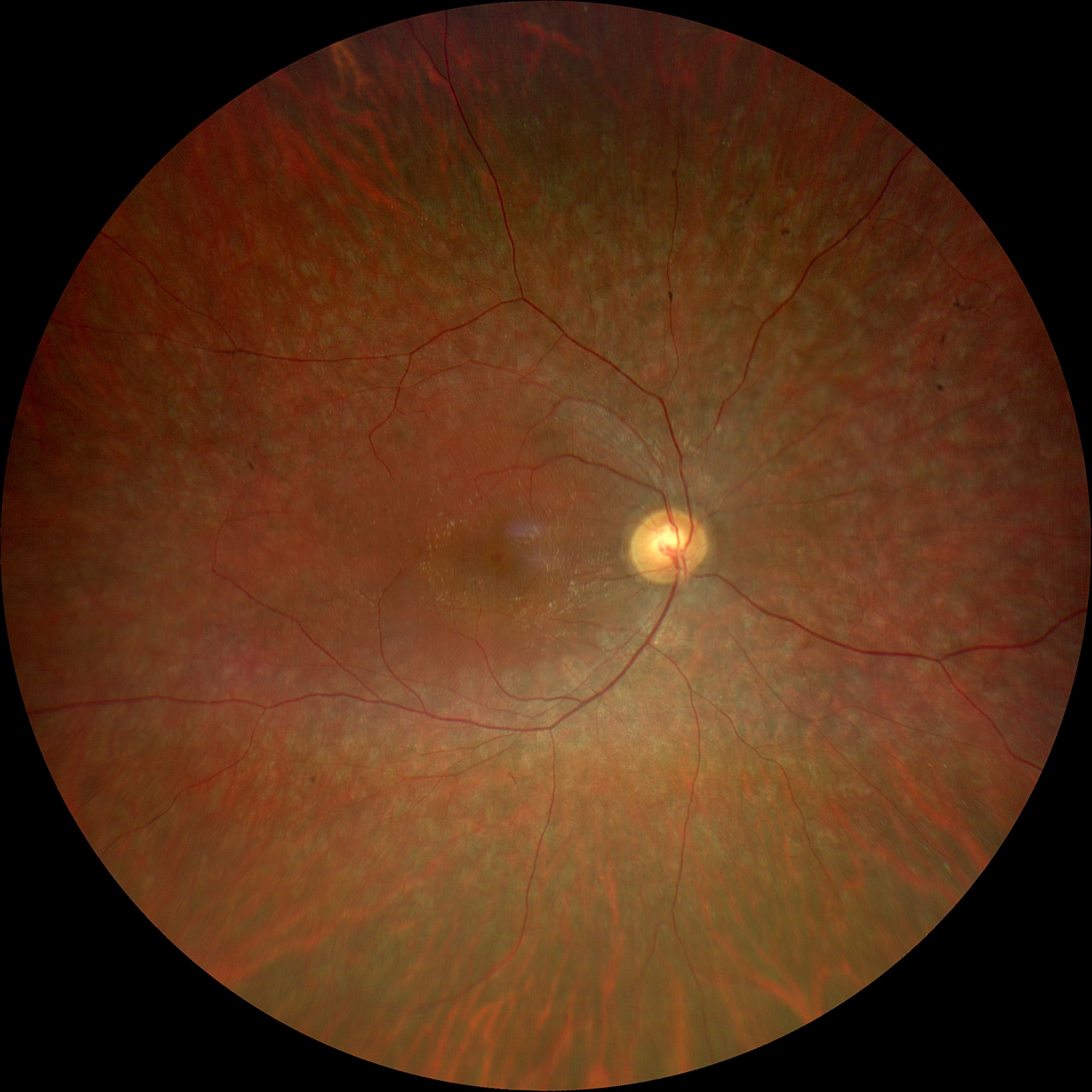

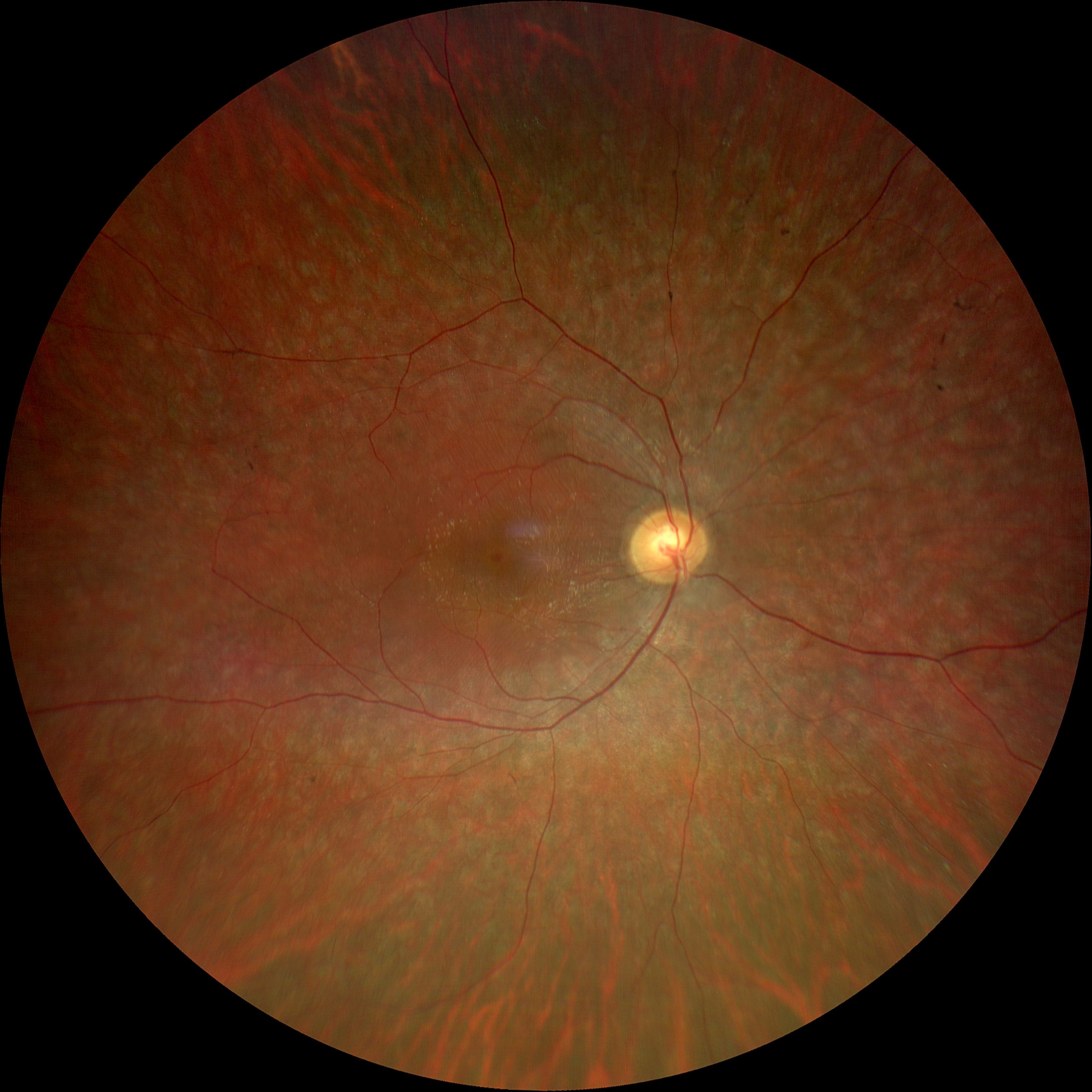

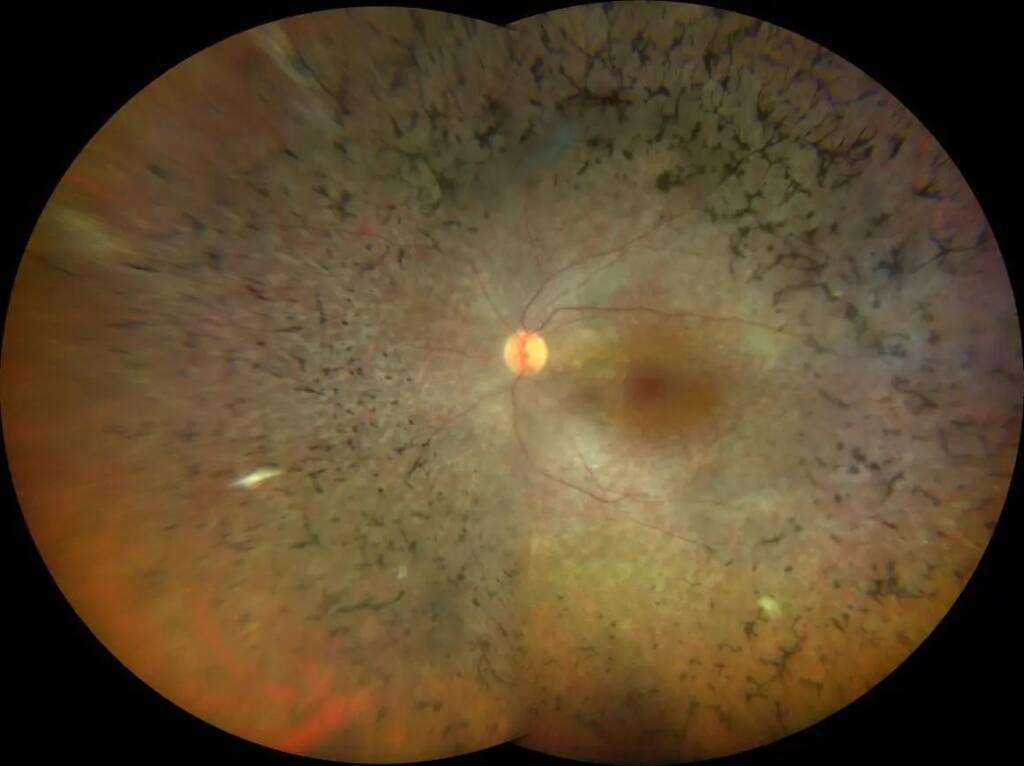

Before typical abnormalities, some patients may present with nonspecific abnormalities such as irregular reflexes from the internal limiting membrane, an enlargement of the foveal reflex and numerous lesions in the RPE. Arteriolar narrowing is also found, the etiology of which is unclear.

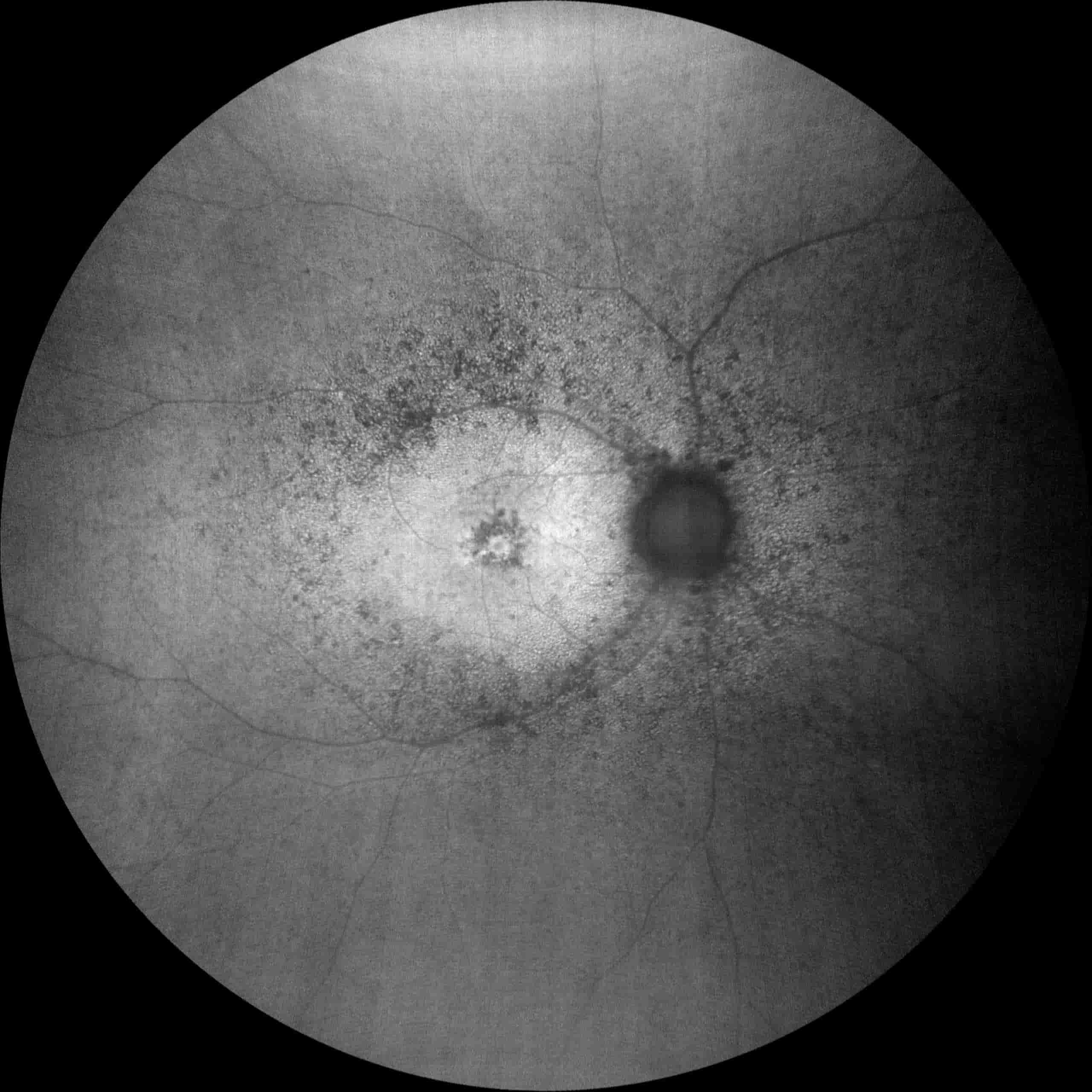

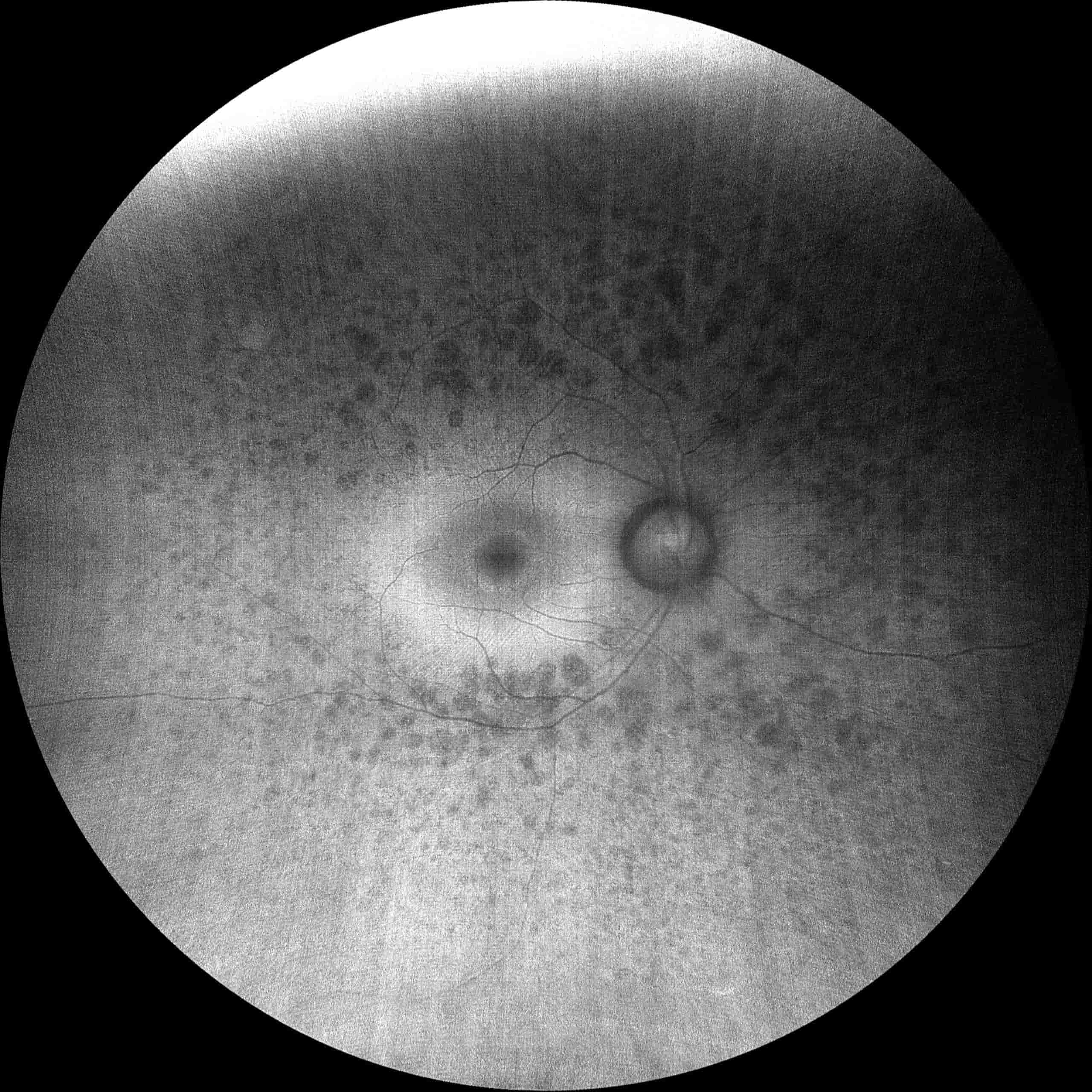

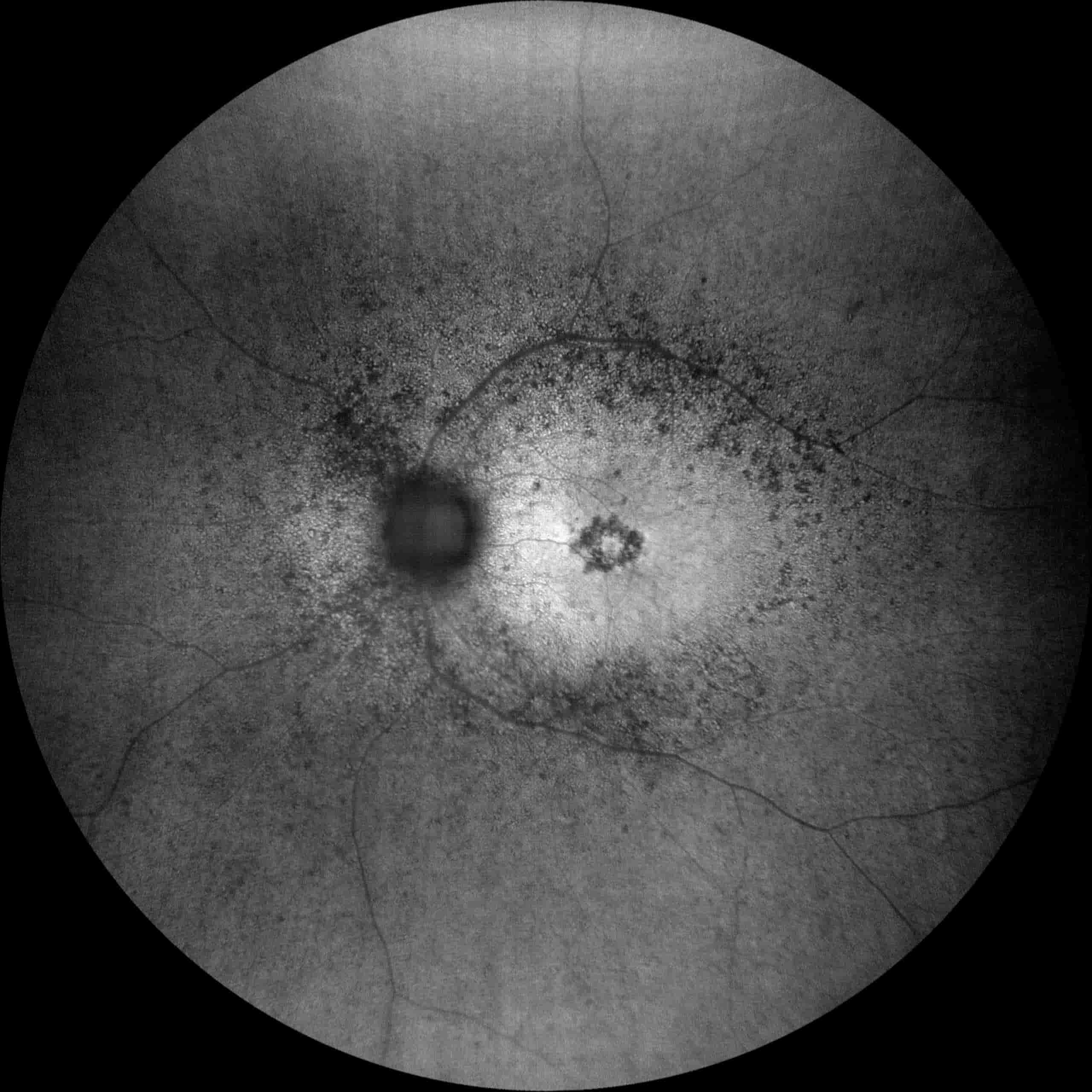

Coarse pigmentary alterations can be observed in the middle retinal periphery, perivascular, in the form of “bony spicules” which gradually increase in density, spreading in an anterior and posterior direction.

Bone spicules consist of RPE cells that break away from the Bruch's membrane and migrate to intraretinal perivascular sites, where they form melanin pigment deposits. The appearance of the mosaic fundus is due to the atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium and the visualization of the large choroidal vessels no longer masked; in addition, the macula may present atrophy, macular cellophane formation (pucker) and cystoid macular edema (CME).

Diagnosis

For patients who report the typical symptoms of Retinitis Pigmentosa, it is essential to carry out an in-depth eye examination associated with specific functional and morphological instrumental examinations. Such as:

- La Computerized Perimetry shows the progressive loss of visual field (CV), characteristic of RP. This visual field loss has a high bilateral symmetry. It usually begins with isolated scotomas in the mid-peripheral areas, which gradually join together to form an annular scotoma in the mid-periphery.

- THEElectroretinogram (ERG) it is an early indicator of the loss of cone and rod function in Retinitis Pigmentosa. The decrease in ERG responses may be evident from the first years of life, although symptoms will appear later.

- La Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) shows a progressive loss of the outer retinal layers and altered distribution of lipofuscin. The first histopathological change in Retinitis Pigmentosa is the shortening of the outer segments of the photoreceptors. This change causes a disorganization of the external retinal layers, initially in the intergitations area, followed by the ellipsoid area and finally by the external limiting membrane.

- THEFluorescence Angiography with Fluorescein (FAG) it is not commonly used for the diagnosis of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Chorioretinal atrophy can be easily observed, initially in the middle retinal periphery, and later in the posterior pole. Although there is usually no delay in filling the retinal vessels, they are attenuated and some leakage is observed.

Treatment

To date, there are still no resolutive therapies that can slow down or stop the progression of retinal atrophy caused by retinitis pigmented, nor is it possible to return the lost vision.

Patients with retinitis pigmentosa are usually prescribed a therapy based on nutritional supplementation with vitamin A, omega 3 and lutein, this can help slow down visual deterioration, but only in the initial stages and in specific forms of the disease.

The greater knowledge of the genetic and molecular mechanisms responsible for the onset of retinitis pigmentosa has allowed the development of new therapeutic strategies. In particular, those based on gene therapy, which aim to "correct the DNA defect" responsible for the disease.

Research has really made great strides in this sense, making it possible to treat diseases that have always been considered incurable, as was the case at the end of 2017 for Leber Congenital Amaurosis dependent on a homozygous mutation of the RPE65 gene.

For retinitis pigmentosa there are several clinical trials of gene therapy, some even of phase II and III, whose encouraging results give us hope that we will soon be able to offer patients with retinitis pigmentosa effective treatments.

Pathology and treatment on video

Do you need more information?

Do not hesitate to contact me for any doubt or clarification. I will evaluate your problem and it will be my concern and that of my staff to answer you as quickly as possible.